“The greatness of Shakespeare is that he remains so contemporary after 400 years.”, said veteran filmmaker Vishal Bhardwaj at the New York Indian Film Festival last week, where he engaged in an extremely insightful conversation with Shakespearean scholar and award-winning author, Professor James Shapiro (Columbia University).

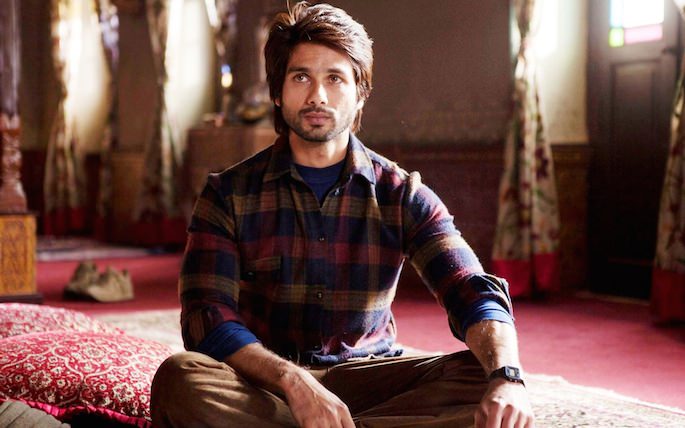

On being asked how he was able to translate the 17th century writings of Shakespeare, which were of a very political nature, into the contemporary reality of the Kashmiri conquest and politics in Haider, Bhardwaj said “It’s about the politics behind humanity, their emotions and their conflicts. The politicians or ministers have changed. But the person behind the minister or the person behind the politician, remains the same. The conflict remains the same.”

Here are the excerpts from the fascinating talk.

On ‘Bismil’ and Shakespearean music

[JS]: I think that Shakespeare plays Hamlet on a razor’s edge. There are many many questions in this play that cannot easily be answered. Is it permissible for his mother to marry his uncle or is that somehow taboo or incestuous? The next question concerns the ghost (of Hamlet’s father). For hundreds of years, in Catholic England, people believed in ghosts. But with the protestant reformation, ghosts were deemed Catholics fantasies; Protestants were no longer supposed to believe in ghosts (except as agents of the devil). So Shakespeare quite brilliantly situates Hamlet’s doubt about the ghost. And the ‘play within a play’ is pointless if Hamlet knows whether the ghost is true or untrue. That was a brilliant scene – the song in the beautiful ancient temple. I thought that was one of the highlights of the film. Can you talk a little bit about the thinking that went into that?

[VB]: We all know that the ‘Mousetrap’ is a very important plot point in Hamlet. So I knew that I was going to exploit that scene. I entered into this film industry as a music composer and later became a film director. When I decided to adapt Hamlet, I knew the mousetrap has to be a big big song number for me. It’s so unusual to have a song in that situation. Shakespeare’s Hamlet brings other actors to act in the ‘play within a play’ scene. But I decided that my Haider is very active himself and he is a very good dancer!

In India, people may forget the film, but if a song becomes popular, they will always remember it. In fact, people may forget the actors, but not the song. We’re so culturally rooted in music and dance. And my bread and butter for my physical body and soul is music. My mentor and the person who writes the lyrics for my films (Gulzar), is a great poet who has been writing for the past 60 years and is a filmmaker himself. So many things came together for me in this film. Kashmir has a beautiful 200-year-old tradition called ‘Bhand Pather’, where they make stories by singing and dancing, although this folk art is almost dying today, because it’s not supported by the State. Still some people, even though their families are very poor, are trying to earn their living through it. All these things came together and then we found this 1400-year-old temple.

[JS]: And the giant puppet – was it a part of this tradition as well?

[VB]: The giant puppet is not a part of the tradition, but the puppet is. So I magnified it!

[JS]: Is it usually all men dancing in that Kashmiri tradition? Or is it men and women?

[VB]: No, it’s mostly men.

[JS]: Let’s talk about music – one of the interests that I think we share. I hated Shakespeare in school and I never studied Shakespeare in university because it was ruined for me by having to read and recite. And it was only when I started seeing plays as a teenager, and seeing how it lived on stage, that I fell in love with Shakespeare. But Music was essential to Shakespeare’s culture in a way that I think it is central, if I’m presumptuous enough to say it, to Indian culture, in a way that it’s not in Anglo-American culture today. And when I read Shakespeare, I hear not only the music of the poetry, but also the songs embedded in the plays. When my students get to those songs, they tend to skip over them, in part because they’re difficult. But that was so exciting in your adaptation of Othello – that you understood how to make the song so central. And in Hamlet, when Ophelia goes mad, she is singing as well, and you picked up and exploited that. That is another way in which you connect the live wires of Shakespeare’s culture to contemporary Indian culture and practice, that makes the play live in ways that many American and British adaptations of Shakespeare on film, just don’t get.

[VB]: Yeah. And I think that’s why subconsciously I connect so well with it. And many times the critics in my own country, when they see these films, they think otherwise. There’s a song in Omkara, which was a major success (Beedi Jalaile) and relaunched me on top of the charts. There’s a term called ‘item number’ in India, where the actress comes and dances without any reason. She doesn’t need to dance for the story, but she does. They thought that I had inserted an item number. But I tried to argue with them that ‘you please read Othello’. This item song is lying there right in the center of it!

On the mother-son relationship – The Oedipus Complex

[JS]: I have to ask you about the mother-son relationship in Hamlet.

[VB]: I think that the ‘oedipus complex’ is a very essential part of Hamlet and it is not very obvious in the play. It’s so much beneath the surface. Because many times I wondered whether it is the interpretation of the critics or am I not reading it right? I don’t know because it’s not there on the surface or in your face. It is very subtle – if you want to make an interpretation of it, you can. So you have to tell me. Do you think that it is very obvious in the play?

[JS]: It’s a very good question and one that I can answer. Sigmund Freud in the late 1890s was struggling with a personal crisis. And his father died. And in a brilliant way of trying to understand and cure and heal himself, he stumbled upon what we now call the Oedipal Complex. But it did not come from reading Sophocles’ play. It came from reading Hamlet. He read Hamlet and he suddenly understood that this was the moment that he had solved the problem of Hamlet, and he called it the Oedipal Complex. But his writings make it clear that it was simply his self-understanding, and this understanding completely transformed the ways in which hamlet was staged, so that by the time Laurence Olivier played it in his famous film, he was steeped in a tradition of seeing the Oedipal Complex at the heart of the character. Even before then, on the American stage – John Barrymore did Hamlet in 1920 and it was very much like the oedipal story that you tell. I should add that Freud based his theory on the idea that Shakespeare wrote this play immediately after the death of his father. Freud read a book which stated that fact. Fifteen years later, the author of that book came out with another book and he said that I got the date wrong – Shakespeare’s father was still alive when he wrote ‘Hamlet’. Freud was so attached to his Oedipal theory that he decided that Shakespeare did not write the play. Somebody else must have. Because only someone who had undergone an Oedipal crisis could have written ‘Hamlet’ –and if Shakespeare hadn’t, then he’s not the author. Freud went to his grave thinking the Earl of Oxford wrote Shakespeare’s plays. But we are now almost a century into a tradition of seeing that aspect of Hamlet’s relationship to his mother that is really central to your story.

[VB]: So then tell me, after Freud discovered this complex through reading Hamlet, did the vision of the scholars, towards Hamlet, change?

[JS]: Yes, absolutely.

[VB]: Oh my God. This is a great revelation for me. I read somewhere that the original source of Hamlet was Amleth? Can you tell us something about that?

[JS]: Yes, sure I can. It’s a medieval scandinavian story about Amleth, who is a very straightforward revenger. Very active. And in the early 16th century, that was translated into Latin and it got picked up in many languages including French. We think that Shakespeare read the French version. But what is at stake in the versions that came down to Shakespeare, is the question of what did Hamlet’s mother know? And how early did she know it? Was she sleeping with her brother-in-law before the story begins, and in different versions, there are different answers to this question. And complicating that wildly is that, there are 3 versions of Shakespeare’s play that come down to us from his lifetime. There’s a version of ‘Hamlet’ that was published in 1603, a very different version published in 1604 and a third version published in 1623. All different. So scholars have to kind of combine them and lead to one story. The earliest version is the one with the much more active Hamlet – much closer to the one you describe. The version that was published last, probably revised by Shakespeare or somebody close to him, makes it more of a family drama than a political drama. Your version is much closer to the family drama of the 1623 version. And only in the earliest version do we get a sense that Hamlet’s mother is more aware of her own guilt –and also a possibility that she was complicit in this.

On Love Triangles

[JS]: Can you talk about how you handled not only the Oedipal dimension, but also the ways in which she might have had this affair with her brother-in-law, even before her husband is captured?

[VB]: Yes. In fact, there is a little scene in my film, when in a flashback, she (Gertrude) goes to her house, where she has found a gun in her son’s bag and she hugs her brother-in-law. And then there is a conversation in front of the father-in-law. The father-in-law tells her that since she has left home, the house feels very sad. And she asks that why don’t you bring Claudius here. To which he says “No no, he’s never going to get married. He doesn’t like any girls.” Gertrude asks Claudius, “Is it true?”. He says “Yeah. All the beautiful girls are taken – like you.” Then there is a silence. And if you notice the father-in-law’s expression, you will see that he is nervous. Because he knew. So that was planted – that he was in love with her even before she got married to his brother.

[JS]: That’s terrific. That moment in the film was great and again very subtle, which I admire. It made me think that you have a special interest in triangles. In a situation where a woman is pursued by more than one man and she must struggle to get herself out of the complications of that triangle.

[VB]: I think so. That’s why I chose Hamlet and Macbeth. In Macbeth, in fact, I made lady Macbeth not the wife of Macbeth, but the mistress of the king, in order to create that triangle. Coming back to that interest – you know in Muslim tradition, it’s not incestuous to marry your dead brother’s wife. It’s a tradition – that you take care of her. The reality of Kashmir is, if a woman’s husband goes missing or has disappeared, whether he is taken by army or he has become a militant – whatever the reason may be, the woman has to wait for four years before she can get married. That’s where the concept of ‘half-widows’ came into that society. They coined the term because you don’t know whether their husbands are dead or alive. And I found it so ironical that in today’s times, in modern day India, these practices are still so active. It’s a very bizarre, very disturbing reality you come across when you visit Kashmir. So I needed to find a parallel to the wedding. Because she can’t get married for four years technically since the husband’s body is not found. So to explore that, we created the situation where Hamlet, when he comes back home for the first time, sees his uncle dancing to his mother’s singing. That was the parallel to give him a shock – your husband just died, and you both are having fun.

On Letting Haider live

[JS]: What about the end of the film? You decided to let Haider live. I study a lot of 16th and 17th century drama, and a lot of these plays – both in England and in Spain, which hold that terrific tradition of revenge drama, if you are the avenger like Haider, you die. There are probably 30 or 40 revenge plays, and in every one of them, the avenger dies at the end. If you go into Spain, every avenger in a Spanish revenge drama of the period, lives! It’s a matter of guilt or shame. And in a guilt culture like Catholic Spain, it’s a form of punishment for somebody to live, than the easy way out – which is to die. So when you were thinking about how you were going to end the film, did you go back and forth on the decision?

[VB]: Actually, to be honest, when I finished the first draft with my co-writer Basharat Peer, Hamlet killed his uncle and he died himself. I have a friend here who teaches screenwriting at Tisch. Her name is Sabrina Dhawan and she’s a fantastic script writer and has collaborated with me on many films. I sent her my script for her reaction and once she read it, she called me and said that everything was fine, but what kind of message is this in the context of Kashmir. Because they’ve been seeing violence for so long now -more than 35 years, that to leave this film on a note that there is no hope for them – only violence and death is going to be their future, would be wrong. I asked her the solution and she said she didn’t have one. So we left it at that and I kept thinking about her point. And then we were on skype again and things came to a point where I was very irritated that I’ve got such a beautiful piece, and just for this one thing, I may have to drop this film. “What do you think I should do? Should Hamlet kill or what?” I asked. Suddenly as I said that, I realized -he doesn’t take revenge. He overcomes his feeling of revenge. It makes him a bigger character! It leaves hope for Kashmir. For everything. And then we started looking back at the whole script.

When I’m writing a script, when I pick up a subject, the first thing I always look at, is the vision. Whenever I read a novel, I first read the last page to see what happens. Because if the resolution is stupid, then there’s no point in writing those 500 pages! I heard a line from a very big writer once, that films always close back from the end. So in Haider, when we decided that he wasn’t going to kill the uncle, we had to plant all these things earlier in the film, and that ‘violence begets violence’ line comes from there.

[JS]: The other thing you do is give Hamlet’s mother far more agency than she gets in Shakespeare’s play. You can’t get more agency than having bombs strapped to your chest. And it’s always bothered me a little bit in Shakespeare’s version that she dies drinking. There was a very famous production in Chicago, 40 years ago, memorable only because Gertrude was an alcoholic. And from the beginning to the end of the play, all she would do is drink martinis. So I think that you balanced out Hamlet’s decision not to be bloodthirsty and not actually take revenge, and you have his mother take revenge. Did that come to you early on?

[VB]: It was there, when we were coming to act three, in the first draft as well. My co-writer is from Kashmir, and he was not very happy with me leaving the film with this hope of ‘violence begets violence’. He said that so much has happened, we have to show the darkest end possible. In this regard, we both had a conflict. One of the arguments was that if we have to leave hope at the end, then why is the mother killing, a few minutes before the end? But I never saw it as the mother avenging for Haider. I saw it as a mother’s love. She knows that her son is going to be killed and she requests Claudius to not kill him. She tries to save Haider till the end and at one point, she realizes that her son is not going to surrender. He’ll get himself killed. That’s when she takes action.

On Censorship

[JS]: One of the things that I studied and research about Shakespeare, is the extent to which Shakespeare lived with censorship. Every play he wrote–icluding ‘Macbeth’ and ‘Hamlet’–he had to submit to the equivalent of the review board, which you had to do, and they would suggest changes. You can have any kind of violence or sex in American films today, and still get a decent rating. But Haider made me feel that Shakespeare’s play and your film share the same constraints of working under censorship, if you want to have a public reach or a wider audience. And I would love for you to speak a little bit about kinds of changes you had to make or chose to make, when this film was presented to the censoring agency in India.

[VB]: I think that the European and American audience is very broad-minded and the law enforcement agencies are very strong. India is a very very beautiful democracy but the law enforcement is not very effective. Even without the censor board or a review committee, the local politics, local vandalism, comes into play. They don’t let the screening take place in a theater. They break the theater and the theater owners are forced to bear the damages. So it’s a problem with the law enforcement in our country, more than the problem of censorship or democracy. Coming back to Haider, this is my most political film and Kashmir is such a volatile and such a sensitive area to make a film on, and I could get away with it. Fortunately for me, the government and the regime didn’t change. The elections had just finished and I knew that if I go in a few weeks later, things may change for me. I was lucky enough to have good members in the review committee because there were so many things that were so sensitive, which they could’ve asked me to cut. It really created a lot of storm in the audiences too. I was called anti-national, anti-army, but I don’t care, because I am not.

On Omkara (Othello)

[JS]: Of all your films, the one character that I thought is most brilliantly realized, and you have terrific actors undoubtedly, is Iago (Ishwar ‘Langda’ Tyagi) in Omkara. You know in modern productions, on the London stage and sometimes on American stage, Othello is the named character, but the best actor now wants to play Iago. So was he the most leading actor in that cast or did he just come across that way?

[VB]: The actor’s name is Saif Ali Khan and his character was called Langda Tyagi. He was indeed one of the biggest stars at that time. And the guy who played Othello (Ajay Devgn) is also a very big star.

[JS]: But in the production, it’s just a very interesting question of whether Othello or Iago is in his own mind, at the center of it.

[VB]: The actor who played Othello is a very generous man, very nice guy. He was also the producer of the film. He said that, ‘I can see that I’m the only one who can play Othello. If I want to play Iago, then who will play Othello?’ He knew what was going to happen after the film releases. The film will be known for Iago, for Saif Ali Khan. And that’s again a very smart thing in Shakespeare’s plays. He names it Macbeth, but it belongs to lady Macbeth. He names it Othello, but it belongs to Iago.

[JS]: Very true. But, it has only really become the case in recent times. And I think especially for Othello. I think lead actors from the 40s and 50s have discovered that Iago is the best role in the play, instead of chasing the main character.

On the unusual success of the trilogy

[JS]: I’ll just say this, and a lot of students and friends know that I don’t really flatter – I’ve seen many adaptations of Shakespeare in the American film industry and the British film industry. From the 1940s on, Shakespeare has been, with the exception of ‘Shakespeare in Love’ and one or two other films, a disaster for Hollywood. But it’s truly not been the case for Bollywood and that is something I try to understand and figure out. Why do you think you have done better than American or English versions of Shakespeare?

[VB]: I think because Shakespeare is not from my country. That’s the main reason. Because you know, when I was making Macbeth, I was very ignorant about the magnitude of Shakespeare’s name. I was making it for my own country, and I thought that it won’t travel beyond that. But I was wrong and the film traveled to different festivals, about 11 years ago. The second time I was doing Shakespeare, I tried to look at the reasons why my adaptation worked in my own country and outside. I realized the bottomline – the main reason was that I was not burdened with Shakespeare’s name. And I was taking liberties as if you know, Shakespeare was my assistant. Unpaid assistant! I didn’t care for what will happen. In my own country, scholars and critics on Shakespeare are very few in number and they don’t even go to watch the films. So I thought, it’ll be fine. That’s how I came upon those things which worked for me. And when I look at other films made on Shakespeare’s plays, I see that they remain very burdened. They’re so conscious of Shakespeare’s work, that they don’t rise beyond it. And it may be too much for me to say, but I felt that in the Hamlet which was made with Ethan Hawke – it was a very nice setting, but it used Shakespearean language. Which makes it so unreal today because that’s not the way people normally speak. So I think this is the reason and, with all due respect, I always remain very true to the soul of the play rather than the text of the play. I was always trying to be very honest to the core of Shakespeare’s work.

[JS]: That’s a terrific answer. And it goes a long way to answer why your films have been so successful. I think, and again I speak only as an outsider, but as an outsider who understands 16th century English culture, that the family dynamics, the simple things like rituals – of weddings, funerals or the food – the eating in your films, you get that. And a lot of the contemporary adaptations don’t seize on that and make it essential to the heart of the film.

‘Haider’ is the third film in Vishal Bhardwaj’s Shakespearean trilogy – the first two being ‘Maqbool’ (Macbeth) and ‘Omkara’ (Othello). It won the People’s Choice Award at the Rome Film Festival and many National Awards in India. Professor James Shapiro teaches English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University and specialises in Shakespeare and the Early Modern period. He has published widely on Shakespeare and Elizabethan culture, and won the 2006 Samuel Johnson Prize as well as the 2006 Theatre Book Prize for his work ‘1599: a Year in the Life of William Shakespeare’. (Wikipedia)