It takes an army (pun intended) of highly skilled artists and technicians to create the movie magic that we experienced with S.S. Rajamouli’s massive blockbuster Baahubali: The Beginning. Thanks to its world-class visual effects, created almost entirely on home soil, the movie has captured the imagination of audiences and critics alike. From wondrous waterfalls with dancing nymphs to the spellbinding war between the Kalakeyas and Mahishmatis, there’s acres of beauty and splendor to behold. Some of that magic, including a significant portion of the war, was created by the talented team at Firefly Creative Studio in Hyderabad.

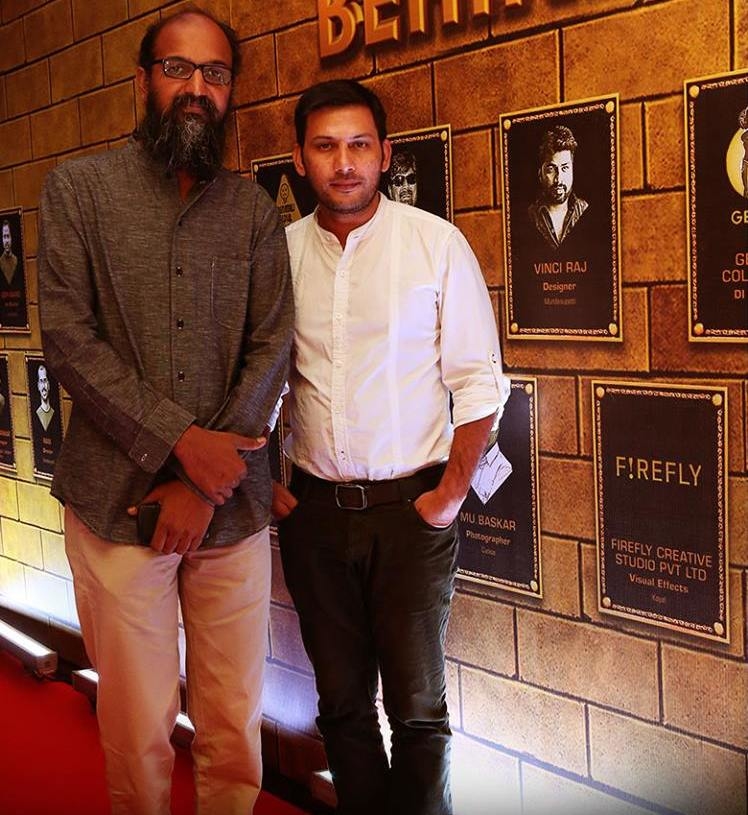

We caught up with visual effects supervisor and founder at Firefly, Sanath PC and visual effects producer Junaid Ullah to get a peek into the making of the spectacular scenes.

[TRM]: Bahubali’s VFX is unlike anything we have seen in an Indian film to date. The war scenes have been compared to the likes of 300 and Game of Thrones. What were your references?

[Sanath]: Doing a war sequence is something that always creates excitement because of the kind of grandeur that you can bring in. Baahubali’s story provided a lot of scope for that. In the story, there’s that stake in the war that whoever kills the Kalakeya warlord, is going to be the next king of Mahishmati. The challenge was to build the action and scenes such that it makes you feel that the victor has indeed done something very heroic.

We saw a lot of films for reference, to understand the scale and help visualize the grandeur. Today, in India too, people have seen all these movies. And we didn’t want them to say that it all looks borrowed from western films. We were really particular about that. Thankfully, Rajamouli is very good with action –both with the choreography and with driving people to make it happen. He really has that command.

“Today, in India too, people have seen all these movies. And we didn’t want them to say that it all looks borrowed from western films.”

[TRM]: Tell us a little about the design and execution of the war sequences.

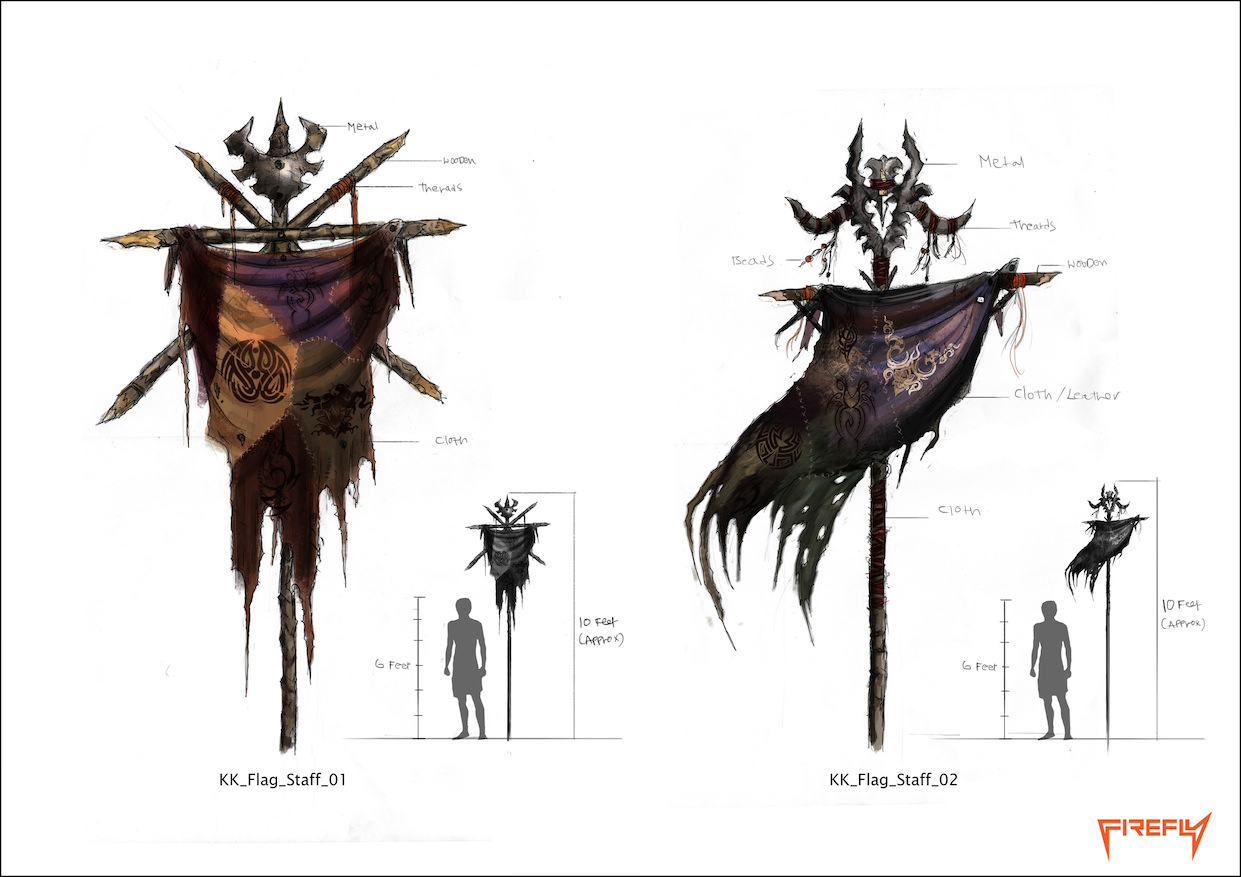

[Junaid]: An important thing with Baahubali, which is a big change over traditional filmmaking, is that, when the director came to us with the story, we told him that instead of doing it the traditional way, which is pre-vis (pre-vizualisation), action breakdown and then going straight into shoot, we should work on “Entertainment Design”. It means building all the characters and their world as intellectual property not just for this film, but for future reference. So we had a lot of briefing sessions to get clarity on the story and narrative. Then we clearly defined each kingdom, character, their backstory and what kind of psychological impact they would have on the story. This way, everything felt much more integrated. For example, in the movie, you just see the Kalakeyas invading. You don’t know where they come from, but they have so much of a backstory which helped us define their characteristics. If we want to show more about them in the sequel or 5 years down the line, the groundwork is already done.

“In the movie, you just see the Kalakeyas invading. You don’t know where they come from, but they have so much of a backstory…”

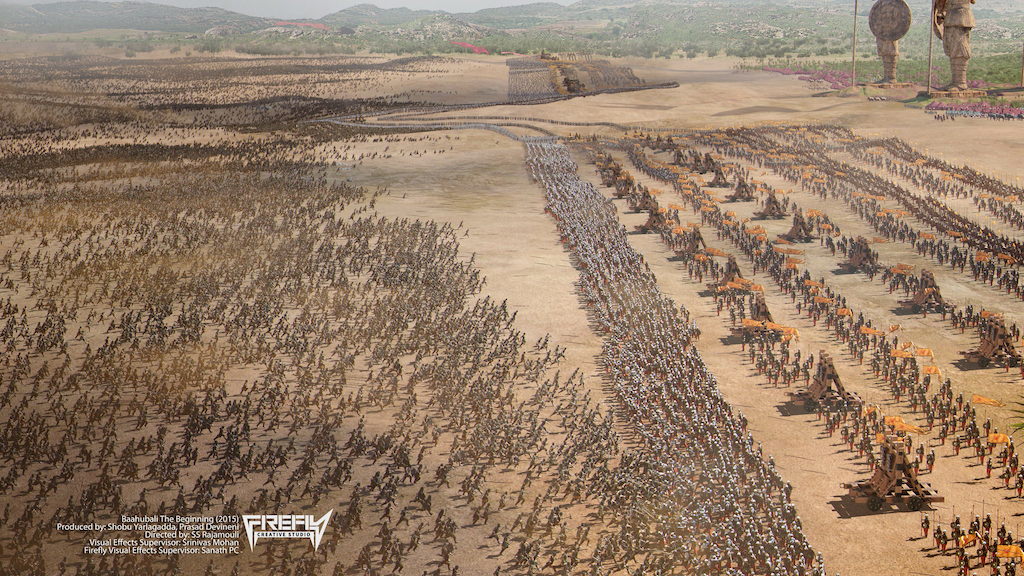

[Sanath]: In terms of war, we started with first deciding the numbers in the armies. The Kalakeyas were supposed to be in huge numbers compared to Mahishmatis. It’s not practical to shoot with 1 to 2 lakh people, so we had to have CGI. Then we had to look into the weapons –we gave a distinct look to the weapons of each army. In the Kalakeyas backstory, they could be a tribe who have fought many wars before and now they are a killing machine. Their weapons are actually tapped in from these different wars, so they look very varied and non-uniform. The Mahishmatis on the other hand are technically advanced. They are highly organized, they have a strong army with well-developed systems of war, and they constantly fight other kingdoms to keep expanding their own. Theirs is one of the most powerful kingdoms in the region. We needed to convey all that visually. If you look at Bhallala Deva (Rana Daggubati), for example, we needed to show that he’s a ruthless killer. That is why he has the chariot with the rotating blades.

Then we had to study traditional war formations and how they were employed. We looked into Arthashastra, which has a very detailed description on war formations. Finally, we had to do some training for the war scenes. When you use traditional extras, they may not move the way soldiers would move in war. When the director says “charge!”, how they run as a group is important. So we called in someone from the military to train them.

[TRM]: In a broad, generalized sense, what parts of the war were CGI and what was real?

[Sanath]: In general, where you have the extreme wide shots with the sweeping cameras, it is entirely CGI. And when you come into the mid-shots where you really see characters fighting and falling, part of it was shot live and the rest was digitally extended. And when it comes to the ground fist-to-fist fight, which is a full-figure or a close-up, it was all live, enhanced by some effects and digital crowds in the background. With the extreme wide shots, we sometimes chose to go even wider, because we could take advantage of that scale to work with less detail on the geometry, without compromising the look.

To be honest, when I look at the shots, I can only see the flaws there. I know that there are so many things to be addressed, so many things to be improved. It is not something that we overlooked, but it is a decision we make to go with ‘what will pass’. Because finally, visual effects is about ‘cheating’. It is not about physical accuracy. As long as the emotions are conveyed, as long as the story flows, it works. Maybe 5 years down the line, it might look outdated technologically, but it should still hold up emotionally.

“Finally, visual effects is about ‘cheating’. It is not about physical accuracy. As long as the emotions are conveyed, as long as the story flows, it works.”

[TRM]: What were some of the challenges during the shoot that you hadn’t planned for?

[Sanath]: The entire shoot happened on open ground. And the biggest problem with an exterior shoot is the weather. The Light keeps changing and there was extreme heat. Putting up the huge green screens had its own problems. In terms of the shoot, we had done quite a lot of pre-vis, so things were well-planned. The fight master, cinematographer, director, VFX supervisor (Srinivas Mohan) were all on the same page because we were looking at the same setup. We did shoot a lot of backup shots so that, if some action shots didn’t work in post-production, we could use something else. But the main problem with a shoot is always the weather and dealing with a large number of people.

[TRM]: How involved is director SS Rajamouli in the VFX process? Did he come by a lot for your review sessions or did he trust your team to deliver what he was looking for?

[Sanath]: The director was fully involved – right from story, to building each character to everything else. His involvement was 100%. For us, the advantage is that we’ve been working with him for quite a few films now. We have a grasp on his style of work and we’ve built a good relationship with him. In the end, it is about how you’re going to make the story work. And with every film, in terms of VFX, we have been able to give him more input to help with the storytelling.

[TRM]: Firefly also worked on some of the creatures in the film and the avalanche sequence. Tell us about that.

[Sanath]: From day one of starting Firefly, our excitement has always been about creating creatures. As of today, we have done all kinds of creatures for films in South India. Snakes, dog, elephants, shark, you name it. Wherever possible, we try to work on them because it is a personal excitement for us. When people say that they can’t tell that the snake in the film was CG, we get a real kick out of that.

“When people say that they can’t tell that the snake in the film was CG, we get a real kick out of that.”

[Sanath]: When it comes to the avalanche, it is not just about the artists who worked on it. It also involves a lot of programming and physics for simulating the snow. With simulations, you try and build it a certain way, but when it renders, it could look totally different. Then you re-iterate on that. And each re-sim can cost you a number of days. That was a big challenge for us.

The avalanche was there in the very first draft of the story. It was the first thing we did pre-vis for. But it kept getting postponed because we weren’t sure if it could be completely CGI and still look right. At one point, they even thought of removing the sequence because of its logistics. But towards the end of the film’s shoot, it came up that we need to have the avalanche because we have a story link there. The director asked us if we could manage to do it in a short time. At that time, we were doing another Tamil film called Kayal, which has a Tsunami sequence. We had a 10 minute long sequence that we had worked on for 8 months. Technically, it was a tremendous achievement for us because it was 100% CGI –big shots of water hitting and destroying the city. That gave us a lot of confidence about handling simulations on that scale. So we said yes, but again the shoot was delayed another month. Finally in December, the shoot took place in Bulgaria. It was the first time in those harsh weather conditions for most of us and it was very very stressful. So practically, we started working on it in post-production at the end of January, since we had to wait for the edited footage to arrive. And we went on till May. Two weeks before the release, we were still delivering the last shots of the avalanche. They were doing sound effects and editing with half-simulated, work-in-progress shots. It was very courageous on their part to go with the sequence because it was a big risk to put it on screen. There was absolutely no time to go back and fix anything, if it didn’t look right.

“Two weeks before the release, we were still delivering the last shots of the avalanche.”

[TRM]: Worldwide, VFX companies today are operating hand-to-mouth. Most of the work is outsourced to the lowest bidder, to countries with the largest tax incentives, resulting in a lot of distress for the artists. What is it like in India? Is it thriving or is it as difficult?

[Sanath]: It is definitely not a rosy picture. Here too, if you really count the companies which have sustained for over 5 years, there are probably only 2 or 3. That shows the difficulty of the situation. But in my perspective, it is also a characteristic of something that is getting evolved. Today the industry and its practices are not well set. Each time we do something new, it disrupts the process that was already in place. Bringing in stability to something that’s evolving, is a slow process. We’re talking of a film industry which took 100 years to reach the state it is at today. Imagine the first 10 years of filmmaking; what it would have been like. The director is trying to make something; he is cranking the camera as well. There’s no cinematographer who comes in and fills that role. To establish that standard, it would have taken a certain amount of time –many generations of cinematographers’ work to arrive at cinematography as it stands today. If you look at CGI in films, it hasn’t been around for over 20 years. People who have worked in the industry for 5 – 6 years consider themselves ‘experts’. Being so nascent, puts you in a vulnerable spot for everyone to exploit you. The VFX industry is full of people who got into it because of their passion. We are constantly trying to prove ourselves – “Oh you can do this, I can do it much better. Let me show you.”, and that has become a habit with us. It is preventing us, as a group, to demand what we deserve.

“We get into too many of these breakdowns and man hours which puts us more and more into trouble. When you try to do it with breakdowns, it appears too simple.”

How does a director convince a producer to make a film when he has nothing in his hand? He says, ‘I have this previous work and I have a story and I can make you money’. The producer doesn’t ask him to prove anything else to arrive at a price. He gets paid based on his previous work. We need to start making demands in that manner. We get into too many of these breakdowns and man hours which puts us more and more into trouble. When you try to do it with breakdowns, it appears too simple. So we really need to re-evaluate how we position ourselves. And that will happen over time as the industry matures.

After a successful stint creating effects for mythological Tamil TV serials and as supervisor for ad films, Sanath’s big break came with the song ‘Roja Roja’ from ‘Kadhalar Dhinam’ (1999, Hindi – Dil Hi Dil Mein). His team worked with renowned cinematographer PC Sreeram to create the rose garden and other effects around the Taj Mahal. Following its success, he went on to start Firefly with his classmates from National Institute of Design in 2000. Firefly Creative Studio has contributed to S.S. Rajamouli’s earlier flims like ‘Chatrapati’, ‘Magadheera’ and ‘Eega’ (Makkhi) as well as Disney’s ‘Anaganaga O Dheerudu’ (Once Upon A Warrior) and Rajnikanth starrer Enthiran (Robot). Their work on the Telugu film ‘Anji’ (2004) won them the National Film Award for Best Special Effects.