Top Rated Films

Anuj Malhotra's Film Reviews

-

Unlike last year’s 10 Cloverfield Lane, Split is not given to a discussion of elaborate strategy: its cage is more existential.

-

The greatest accomplishment of the film — as of say, a Baby’s Day Out — is their assimilation of the diverse landscapes of the city itself.

-

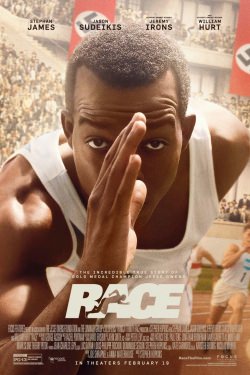

Hopkins’ film is ultimately a successful interpretation of actual historical event. It manages to resist an overstatement of Owens’ achievement and instead chooses to abandon its sport-film façade and adopt the stance of a period-film, wherein a significant historical event may yield more than one hero.

-

The film emerges ultimately as a modern-day moral-parable about a checklist of virtues: acceptance, self-discovery, family, belonging to one’s roots and so forth. It is still useful, however, for how it is so typical — its study can reveal a template for how most mainstream animation films are made, always in relation to the other films produced by the same industry.

-

Villeneuve directs it with a super heavy-hand: the tone belongs to an occult ceremony: everything is supersober, no one is meant to laugh and all grand proclamations (whether a line of dialogue or the sight of mutilated dead bodies suspended from a bridge) are followed by droney, town-hall music. While this maybe appropriate for the subject, it is also typical of Hollywood movies about individual protagonists who discover the ugliness inherent in a foreign landscape.

-

While Adam Driver plays Jamie, the young blowhard well enough, Josh needed an actor who can infuse his being with cruelty, envy and contempt but then render these vices entirely human.

Unfortunately, Ben Stiller plays him with a cocksureness that strips away the confusion his character is mired in and makes him appear like a glorious party-pooper, nothing else.